Full Text

Introduction

Onychomycosis is a chronic fungal infection of the fingernails or toenails, which is characterized by discoloration, thickening of nails and separation from the nail bed. Onychomycosis usually begins from distal or lateral edge of the nails and under the nail there is accumulation of cheesy, keratotic debris. Onychomycosis affects approximately 5% of the population worldwide and the prevalence in India is reported to vary from 0.5% to 5% [1]. Various factors predispose onychomycosis like nail trauma, diabetes, hyperhydrosis, improper nail hygiene, HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) infection, regular use of occlusive footwear, smoking, occupation and climate influence etc [1]. Onychomycosis show male preponderance and more commonly affect toenails than fingernails as the toenails grow slowly, have less blood supply and are often confined in dark and moist condition.

Onychomycosis can be caused by dermatophytes, yeasts or non-dermatophyte moulds. Dermatophytes are the most frequently implicated causative agents and causes approximately 90% toenails and 50% fingernails infection [2]. Among dermatophytes, Trichophyton rubrum and Trichophyton mentagrophytes, Trichophyton verrucosum, Epidermophyton floccosum are the common agents [3]. Candida species particularly Candida albicans is the most common yeast associated with onychomycosis, followed by other species such as Candida krusei, Candida parapsilosis, Candida glabrata, Candida tropicalis [4]. The yeasts are mainly present in the tropical and subtropical regions and usually infect the persons whose hands are submerged in water. Non-dermatophyte moulds such as Aspergillus niger, Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus fumigatus, Curvularia species, Penicillium species, Rhizopus species, Fusarium species, Geotrichum candidum, Acremonium, Alternaria, Bipolaris, Scopulariopsis brevicaulis, etc can also be sited as causative agents of onychomycosis [5].

Onychomycosis is not a life-threatening condition but it can have significant negative effects on patient's emotional, social and occupational functioning and can cause permanent damage to the nails of the patient. The affected nail can also serve as a chronic reservoir giving rise to repeated fungal infections and can communicate the fungal infection to family members which poses an important public health problem.

Treatment regimen and duration depends on the etiological agent causing onychomycosis. So, for the timely initiation of appropriate and effective treatment knowledge of etiological agents causing onychomycosis is required. This study was conducted to improve the knowledge of demographic and mycological profile of onychomycosis in a tertiary care hospital in Bareilly.

Material and methods

The study was conducted after the approval of institutional ethical committee. Nail clipping or scraping was taken from 74 clinically suspected onychomycosis patients, who have visited the Dermatology outpatient department during the period of July 2019 to March 2020. The patients who were on systemic or topical antifungal therapy at the time of sample collection or have history of onychodystrophy due to congenital defect or who had not given their consent, were excluded from the study. The detailed history of the patients including socio-demographic particulars, presenting complaints, duration of infection, treatment history, occupation, predisposing factors like nail trauma, diabetes, HIV infection and prior use of antifungals were taken. Nails were examined for discolouration, thickening, lustre, brittleness, pitting and presence of paronychial inflammation (Figure 1).

Figure 1a-c: Clinical presentation in patients of onychomycosis.

Nail scraping or clipping of suspected nails were collected in brown paper envelope after cleaning the affected area with 70% alcohol and transported to the mycology laboratory for identification.

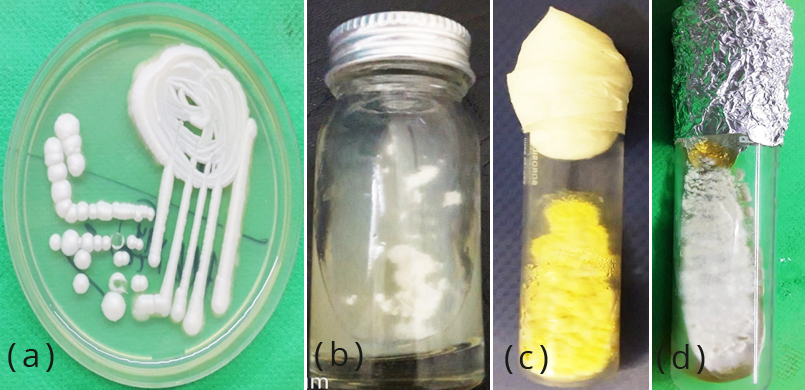

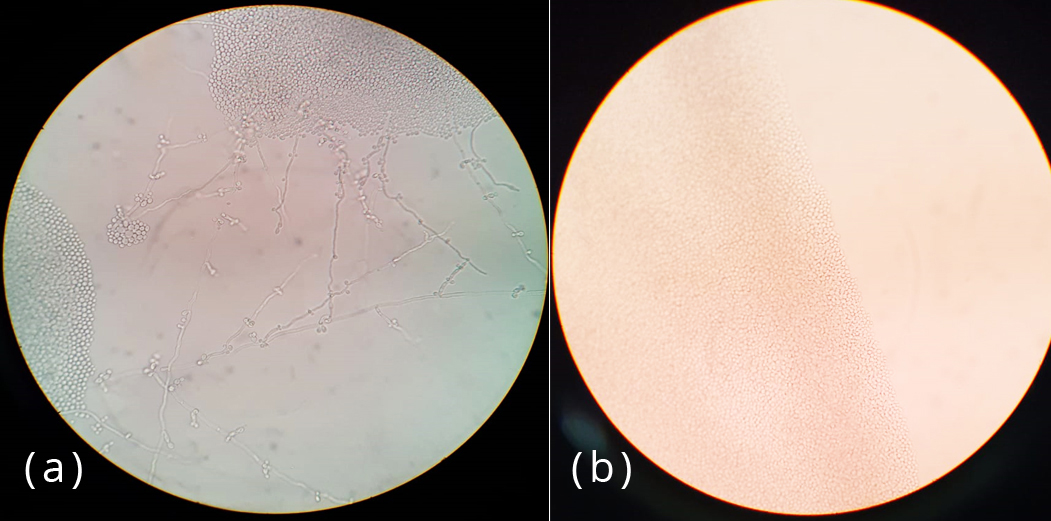

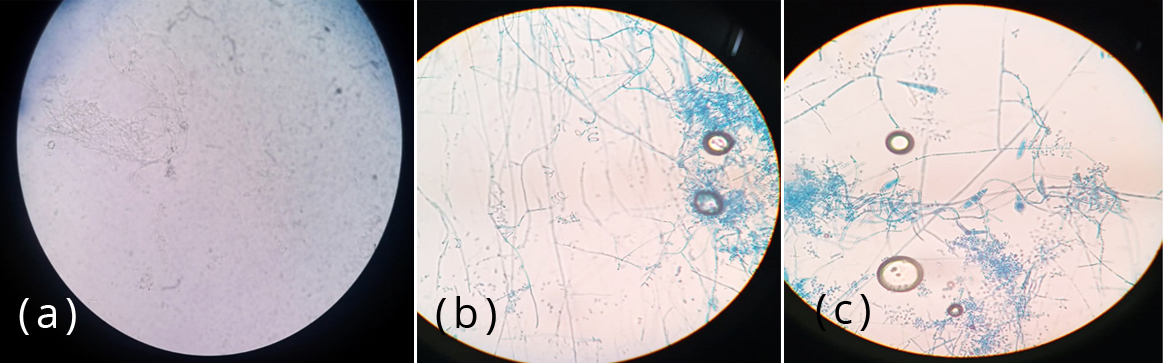

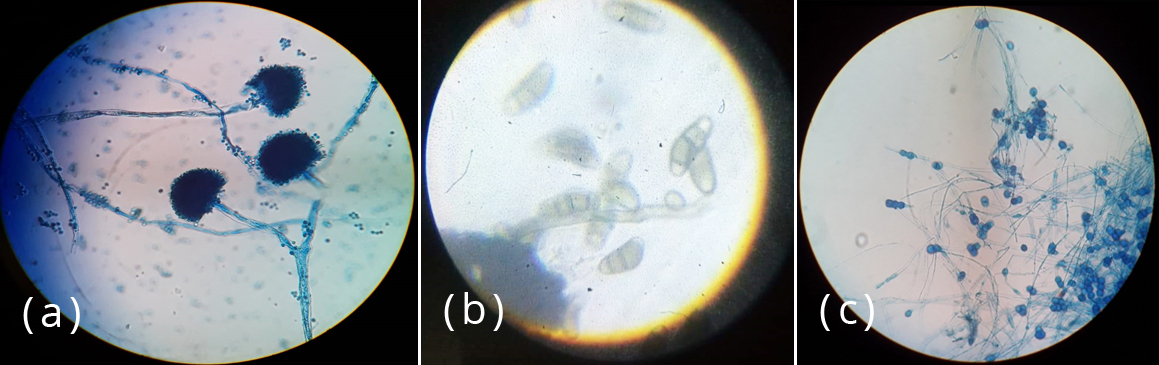

The specimens were processed by direct microscopic examination using 20% KOH and isolation by culture. Each of the samples was inoculated into two slants of modified Sabouraud’s dextrose agar with gentamycin and cycloheximide. Cultures were incubated at 25oC and 37oC and examined daily for first week and twice a week for 4 weeks. Each of the SDA tube was observed for texture, colony morphology, obverse and reverse pigmentation (Figure 2). If growth was present, a LPCB teased mount was prepared and examined under microscope. Yeast-like growth of the isolates were examined by Gram staining, germ tube test and inoculated onto Hichrome agar and cornmeal agar for identification of Candida species (Figure 3). Slide culture was put up for mycelial isolates to study the undisturbed detailed morphology of the fungi. Biochemical reactions such as urease test was performed for differentiation of dermatophytes (Figures 4&5).

Figure 2: Growth on SDA (a) white creamy colonies of Candida spp. (b) white cottony colonies of Fusarium, (c) yellow granular colonies of Aspergillus flavus (d) tan cottony colonies of Trichophyton mentagrophytes.

Figure 3: Growth on cornmeal agar (a) Blastoconidia arranged in singly and small groups along long pseudohyphae in C. albicans (b) Oval yeast cells without pseudohyphae in C. glabrata.

Figure 4: Thin, branched, hyaline septate hyphae of dermatophytes in (a) KOH mount and LPCB stain along with (b) spiral hyphae and (c) micro and macroconidia.

Figure 5: LPCB stain showing (a) branched septate hyhae along with conidia covering two third of the vesicle in Aspergillus flavus, (b) Brown, curved, transversely septate conidia in Curvularia (c) Septate hyhae with one celled globose conidia in Scopulariopsis.

Results

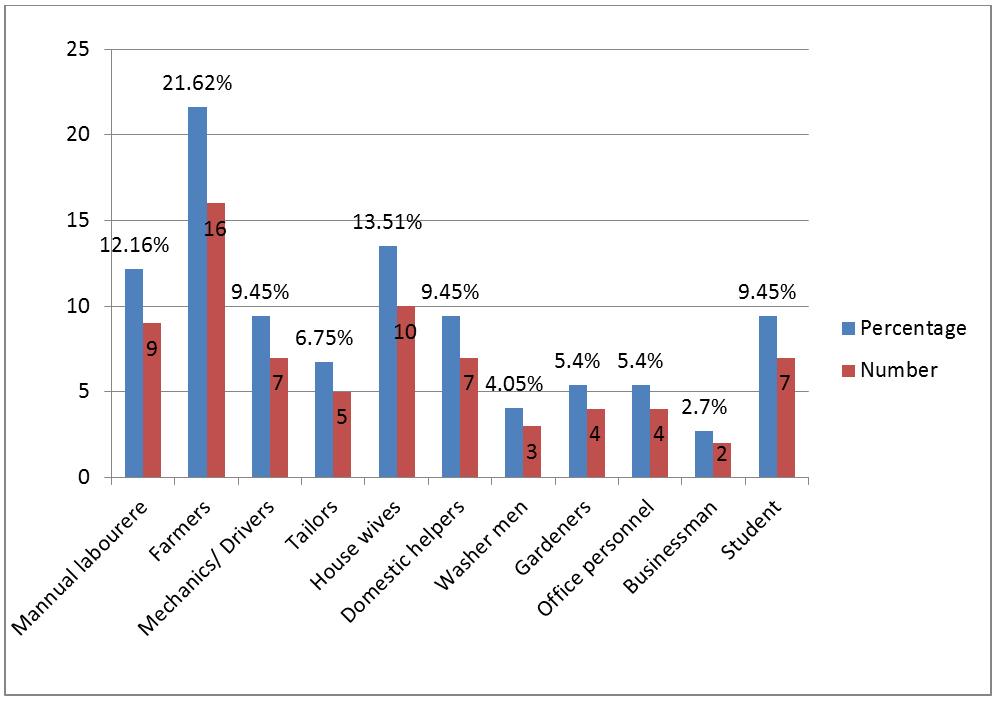

Out of 74 cases, maximum patients (35.1%) were observed in 21-30 years age group followed by 31-40 years (21.6%) and 41-50 years (10.8%). Ten patients were above 50 years age. We have found no patient of age less than ten years. In our study, we have observed male preponderance (56.76%). Toe nails were the most frequent anatomic site involved in 31 (41.89%) cases followed by finger nails in 18 (24.32%) cases and both were affected in 5 (6.75%) cases. In our study population, cases were occupationally found associated with increased physical activity and wet work (Figures 6).

Figure 6: Occupational wise distribution of patients.

Among our study population, smoking (10.8%) emerged as the major risk factor followed by animal handling (8.1%), diabetes (5.4%), steroid induced immunosuppression (2.7%), peripheral vascular disease (1.3%) and family history (1.3%). Distal and lateral subungual onychomycosis (78.3%) was observed as the commonest clinical type of onychomycosis followed by proximal subungual onychomycosis (10.81%), superficial white onychomycosis (1.35%), total dystrophic onychomycosis (1.35%) and paronychia (6.7%).

Direct microscopy under KOH (Potassium hydroxide) mount was positive in 49 (66.22%) cases and fungal culture was positive in 44 (59.46%) cases (Table 1). Dermatophytes (43.47%) were the predominant group isolated followed by Candida spp. (32.60%) and non-dermatophyte moulds (23.91%) and in the finger nails, Candida spp. 6 (11.54%) were the predominant group isolated followed by dermatophytes 4 (7.7%) and non-dermatophyte moulds 3(5.7%) (Table 2).

Table 1: Direct microscopic examination and culture of the clinical specimens.

|

Direct examination

(KOH mount)

|

Fungal culture

|

Total

|

|

Positive

|

Negative

|

|

Positive

|

42 (56.7%)

|

7 (9.46%)

|

49 (66.22%)

|

|

Negative

|

2 (2.7%)

|

23 (31.1%)

|

25 (33.78%)

|

|

Total

|

44 (59.46%)

|

30 (40.56%)

|

74

|

Table 2: Various etiological agents isolated from the patients of onychomycosis.

|

|

Fungal agent

|

No. of isolates (%)

|

|

Dermatophytes

|

|

|

Trichophyton mentagrophytes

|

9 (19.56%)

|

|

|

Trichophyton rubrum

|

5 (10.86%)

|

|

|

Trichophyton tonsurans

|

3 (6.52%)

|

|

|

Epidermophyton floccosum

|

3 (6.52%)

|

|

|

Total

|

20 (43.47%)

|

|

Candida species

|

|

|

Candida albicans

|

4 (8.69%)

|

|

|

Candida krusei

|

5 (10.86%)

|

|

|

Candida glabrata

|

3 (6.52%)

|

|

|

Candida parapsilosis

|

3 (6.52%)

|

|

|

Total

|

15 (32.60%)

|

|

Non-dermatophyte moulds

|

|

|

Fusarium spp.

|

5 (10.86%)

|

|

|

Aspergillus niger

|

2 (4.34%)

|

|

|

Aspergillus flavus

|

1 (2.17%)

|

|

|

Aspergillus terreus

|

1 (2.17%)

|

|

|

Scopulariopsis brevicaulis

|

1 (2.17%)

|

|

|

Curvularia spp

|

1 (2.17%)

|

|

|

Total

|

11 (23.91%)

|

Among dermatophytes, Trichophyton mentagrophytes was isolated in 9, Trichophyton rubrum in 5, Trichophyton tonsurans in 3 and Epidermatophyton floccosum in 3 patients. While among Candida, C. krusei was isolated in 5 cases followed by C. albicans, C. glabrata and C. parapsilosis.

Non-dermatophyte moulds were isolated in 11 patients, Fusarium spp. in 5 patients, Aspergillus niger in 2 patients, A. flavus in 1 patient, A. terreus in 1 patient, Scopulariopsis brevicaulis in 1 patient and Curvularia spp. in 1 patient.

Discussion

Onychomycosis is a chronic fungal infection of nails. It is not serious in terms of morbidity, physical sequelae and mortality although, it has significant negative impact on patient's emotional, social and occupational functioning given its infectious nature, aesthetic consequences, chronicity and therapeutic difficulties.

The present study was conducted in an attempt to estimate the prevalence and describe epidemiology, risk factors and etiological agents of onychomycosis in patients reporting to a tertiary care hospital in Bareilly, Uttar Pradesh. In this study, the prevalence of onychomycosis has been estimated to be 59.46% among the patients attending Dermatology outpatient department. Other workers from different geographical locations had reported similar prevalence of fungal aetiology in patients of clinically diagnosed as onychomycosis like 51.7% in Kolkata [6], in Delhi 54.5% [7] and 58.4% [8] in Mumbai.

The present study showed that onychomycosis is more common in age 21-40 years (56.7%) and less common in age above 60 years (4.23%) which is comparable to the study done by Satpathi et al [9] and Lone et al [10]. This could be related to trauma following occupational and sporting activities or use of occlusive footwear. Moreover, younger population is usually cosmetically conscious and therefore seeks early and frequent dermatological consultation.

Some studies have reported that onychomycosis is more prevalent in women because of their more involvement in wet work [11-13]. However, in our study, we have observed male preponderance (64.86%) which could be due to their increased outdoor activities and occupation related injuries which make them more vulnerable to trauma and subsequent fungal infections [6, 13-15].

Fingernails (51.35%) were found to be more affected as compared to toenails (41.89%) and this finding is comparable to that reported by other authors [15, 16]. More involvement of fingernails in onychomycosis may be because of increased chances of acquiring trauma and fingernails infection is more likely to arouse the patients concern as compared to toenails infection, driving them to seek medical attention. Our study has demonstrated more involvement of fingernails in females (27.02%) and toenails in males (35.13%); similar finding has also been reported by Kaur et al [15, 17], and Ashokan et al [18].

We have analysed the association of occupation with the incidence of onychomycosis and have observed that the majority of patients in our study were associated either with increased physical activity or wet work. Similar finding is observed in other studies also [8, 9, 17]. Farmers (26.62%) were the predominantly affected group and this can be attributed to repeated trauma to nails and contact with the saprophytic fungi of soil.

Beside occupation, diabetes mellitus (5.4%), smoking (10.8%), peripheral vascular disease (1.3%), animal handling (8.1%) and family history emerged as risk factors for development of onychomycosis in our study. Similar association has been seen in studies conducted by Yadav et al [8] and Sharma et al [19].

The two conventional methods for fungi identification are direct microscopy under KOH mount and fungal culture. The microscopy is more sensitive for demonstrating the presence of fungi, but for the isolation and identification of the specific genus and species of the pathogen, fungal culture is required which is not always fruitful.

Our study revealed presence of fungal elements in 66.22% samples on direct KOH mount examination. This finding was lower than the results of various researchers [14, 19, 20] who reported mycological positivity of 81.8%, 75.23% and 82.35% respectively while this may be considered higher when compared with other studies [8, 15] showing mycological positivity of 34% and 24.8%, respectively. In the present study, culture proven onychomycosis was present in 59.46% patients and this is nearly concordant with the studies conducted by Grover et al [21] and Kaur et al [22] showing culture positivity 62.7%, 60%, and 60.2%, respectively. In our study, both culture and direct KOH mount examination were positive in 56.7% samples hence both tests can be used as complementary to each other.

Dermatophytes was the most commonly isolated fungi (43.47%) followed by Candida species (32.60%) and non-dermatophyte moulds (23.91%). Many other studies conducted in different parts of India and abroad have also reported dermatophytes as the commonest cause of onychomycosis [21, 23-26].

Among dermatophytes, Trichophyton mentagrophyte (19.96%) was the predominant species followed by T. rubrum (10.86%). The finding is similar to studies done by Bhatia et al [24] and Debbarma et al [25]. While in several other Indian studies, T. rubrum was elicited as the commonest dermatophyte [14, 26].

Among non-dermatophyte moulds, Fusarium spp. (10.86%) was the predominant isolate. Leelavathi et al [26] have also reported similar finding in their study. It was observed that NDMs are mostly isolated in older patients with impaired blood circulation, poor personal care, lower immune response and systemic diseases like diabetes.

Conclusion

Onychomycosis is no longer considered just a simple cosmetic nuisance confined to the nails as it can lead to physiological and occupational problems thus impairing quality of life. Clinical diagnosis of onychomycosis is difficult and challenging as the type of nail changes cannot be taken as a reliable marker for predicting the causative agent thus microbiological confirmation is needed for the same. Therapeutic options available for the treatment of onychomycosis have not been proven to be universally efficacious, duration of therapy is long and more over the drugs used are not very safe. So, it is preferable to establish the aetiology of infection with laboratory methods before the treatment has begun. This will not only help the treating physician in choosing the treatment regime, but will also be useful in predicting the prognosis.

Conflicts of interest

Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

[1] Ahmad M, Gupta S, Gupte S. A clinico-mycological study of onychomycosis. Egyptian Dermatology Online Journal. 2010; 6(4):1-9.

[2] Clayton YM. Clinical and mycological aspects of onychomycosis and dermatomycosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992; 17(Suppl 1):37–40.

[3] Jesudanam TM, Rao GR, Lakshmi DJ, Kumari GR. Onychomycosis: A significant medical problem. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2002; 68(6):326–329.

[4] Elewski BE. Onychomycosis: Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998; 11(3):415–429.

[5] Ellis DH, Watson AB, Marley JE, Williams TG. Non-dermatophytes in onychomycosis of the toenails. Br J Dermatol. 1997; 136(4):490–493.

[6] Suryawanshi RS, Wanjare SW, Koticha AH, Mehta PR. Onychomycosis: dermatophytes to yeasts: an experience in and around Mumbai, Maharashtra, India. Int J Res Med Sci. 2017; 5(5):1959–1963.

[7] Gupta M, Sharma NL, Kanga AK, Mahajan VK, Tegta GR. Onychomycosis: Clinico-mycologic study of 130 patients from Himachal Pradesh,India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2007; 73(6):389–392.

[8] Yadav P, Singal A, Pandhi D, Das S. Clinico-mycological study of dermatophyte toe nail onychomycosis in New Delhi, India. Indian J Dermatol. 2015; 60(2):153–158.

[9] Satpathi P, Achar A, Banerjee D, Maiti A, Sengupta M, et al. Onychomycosis in Eastern India -study in a peripheral tertiary care centre. Journal of Pakistan Association of Dermatologists. 2013; 23(1):14–19.

[10] Lone R, Bashir D, Ahmad S, Syed A, Khurshid S. A Study on clinico-mycological profile, aetiological agents and diagnosis of onychomycosis at a government medical college hospital in Kashmir. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013; 7(9):1983–1985.

[11] Sarkar M, Ray R, Halder P, Ghosh A, Chatterjee M. Clinico-mycological profile of onychomycosis. IOSR journal of dental and medical sciences. 2016; 15(9):78–83.

[12] Gupta AK, Ryder JE, Johnson AM. Cumulative meta-analysis of systemic antifungal agents for the treatment of onychomycosis. Br J Dermatol. 2004; 150(3):537–544.

[13] Gelotar P, Vacchani S, Patel B, Makwana N. The prevalence of fungi in fingernail onychomycosis. JCDR. 2013; 7(2):250–252.

[14] Harika DR, Usharani A. A Study of onychomycosis in Krishna district of Andhra Pradesh, India. Our dermatol online. 2015; 6(4):384–391.

[15] Kaur R, Kashyap B, Makkar R. Evaluation of clinicomycological aspects of onychomycosis. Indian J Dermatol. 2008; 53(4):174–178.

[16] Reddy KN, Srikanth BA, Sharan TR, Biradar PM. Epidemiological, clinical and cultural study of Onychomycosis. American Journal of Dermatology and Venereology. 2012; 1(3):35–40.

[17] Kaur T, Puri N. Onychomycosis- A clinical and mycological study of 75 cases. Our Dermatol Online. 2012; 3(3):172–177.

[18] Ashokan C, Bubna AK, Sankarsubramaniam A, Veeraraghavan M, Rangarajan S, et al. A clinicomycological study of onychomycosis at a tertiary health-care center, Chennai. Muller J Med Sci Res. 2017; 8(2):74–81.

[19] Sharma P, Sharma S. Non-dermatophytes emerging as predominant cause of onychomycosis in a tertiary care centre in rural part of Punjab, India. J Acad Clin Microbiol. 2016; 18(1):36–39.

[20] Veer P, Patwardhan NS, Damle AS. Study of onychomycosis: prevailing fungi and pattern of infection. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2007; 25(1):53–56.

[21] Grover C, Reddy BS, Chaturvedi KU. Onychomycosis and the diagnostic significance of nail biopsy. J Dermatol. 2003; 30(2):116–122.

[22] Kaur R, Kashyap B, Bhalla P. A five-year survey of onychomycosis in New Delhi, India: Epidemiological and laboratory aspects. Indian J Dermatol. 2007; 52(1):39–42.

[23] Kumar R, Pannu S, Kumar M, Yadav OM. The prevalence onychomycosis in North Western region of Rajasthan. IHRJ. 2018; 1(10):323–329.

[24] Bhatia VK, Sharma PC. Epidemiological studies on Dermatophytes in human patients in Himachal Pradesh, India. Springer plus. 2014; 3:134.

[25] Debbarma M, Barman D, Majumdar T. Clinico-mycological profile of onychomycosis in a Tertiary Care Centre of Tripura. J. Evolution Med. Dent. Sci. 2016; 5(71):5180–5185.

[26] Leelavathi M, Izar MN, Adawiah J. Common microorganisms causing onychomycosis in tropical climate. Sains Malaysiana. 2012; 41(6):697–700.